Introduction

Academic Library

Instruction has grown dramatically in current times. What was once a card

catalog of librarians searching for and delivering specific books to students

has become an online experience of self service, utilizing all information

formats for research purposes. With reference services changing, the need for

accurate instruction of library services and research skill development has

changed as well. Instruction librarians use many different teaching methods for

their students, both in one-shot instruction and in long-term instruction.

In current times, these

different methods have taken a more active role rather than lecture based.

Since the late 1800’s, library instructors have noted how lecture-based

learning has failed students. “The assumption that library instruction should

be lectured based probably has driven the opposition of many academic

librarians to library instruction. After all, if lecturing to students about

library use does not work, why do it? (Lorenzen, 2001).” Instead, many academic

libraries are turning toward active learning in the library classroom for

instruction purposes.

What is Active Learning?

|

| Source |

Active learning, in essence, employs instructional methods

opposite to that of passive learning. Passive learning teaching style engages a

lecture-based learning with heavy note taking and memorization. It relies

strictly on a one-way learning from teacher to student (Holderied, 2011).

Active learning, on the other hand, “has struck a chord with educators for the

way that it enables instructors to accommodate varying learning styles and

encourage active participation of students” (Bonwell and Eison, 1991). It takes

the student beyond the role of the listener and engages them to be more

proactive in their learning. By employing a variety of techniques, including

small group discussion, hands-on activity, and role playing, the students

become involved in discovering for themselves the answers to their research and

library needs. This allows them to have the first-hand knowledge of the

necessary skills and the ability to utilize them in their academic careers.

The

push for active learning in the library classroom in modern times have come

from three voices. In 1991, David Johnson, Roger Johnson, and Karl Smith wrote

a book entitled “Active Learning: Cooperation in the College Classroom” and

began their campaign promoting active learning as an essential part of library

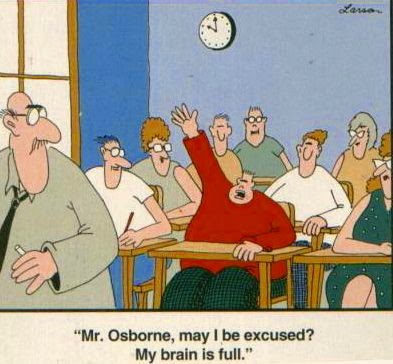

instruction. Their findings revealed that students have trouble focusing on

lectures and that their focus weakens over the time period of the class. They

also found that students found lectures, frankly, boring. Lectures might

promote the rote memorization of facts but do not utilize a student’s higher

functioning such as their analyzing and synthesizing skills (Lorenzen, 2001).

Drueke and the One-Shot Active Instruction

In 1992, J.

Drueke wrote an article entitled “Active Learning in the University

Library Instruction Classroom.” Within the article, he notes

four barriers of active learning in the library setting. For one, librarians

usually see a group of students only once and are not their usual teachers.

This ‘one-shot’ instruction makes it difficult to fit all the necessary ideas

into the short time frame without lecturing. Students also find librarians to

not be a source of information because they are not their usual teachers. This

creates a sort of mental block from forming the information presented to them

during the instruction. Another barrier is the sheer lack of time to cover all

the material necessary in these ‘one-shot’ instruction. Many librarians feel

that an active learning approach will take away precious time that is needed to

actually teach the material. Finally, the instruction librarian does not have

total control of the class and their material. The primary teacher usually

comes into the instruction time with requirements and suggestions of topics to

cover, putting the librarian in a more subordinate teaching role. The materials

covered would, in theory, be controlled completely by the library instructor.

However, any good library instructor would know to structure their teachings to

fit the needs of the students.

|

| Source |

Another large

obstacle is the instruction librarian’s reluctance to employ active learning in

the classroom.

C. E. Mabry said: I

found, however, that the instructor's first step in applying cooperative

learning techniques involves rethinking his/her role in the classroom. It is

not easy to give up lecture time in a 50 minute BI session. But one of the

primary tenets of cooperative learning is that, if instructors are prepared to

give up some control, students will learn more and retain that knowledge

longer. (p 183)

In

order to combat this lack of control and the desire to stay with the

lecture-based learning, Drueke came up with nine strategies of active learning

for librarians:

I. Talking informally with students as they arrived for class.

2. Expecting that students would participate and acting accordingly.

3. Arranging the classroom to encourage participation including putting

chairs in a cluster or circle.

4. Using small group discussion, questioning, and writing to allow for

non-threatening methods of student participation.

5. Giving students time to give responses, do not rush them.

6. Rewarding students for participating by praising them or paraphrasing

what they say.

7. Reducing anonymity by introducing yourself and asking the students for

their names. Ask the class to relate previous library experiences as you do this.

8. Drawing the students into discussions by showing the relevance of the

library to their studies.

9. Allowing students time to ask questions at the end of class.

These

strategies, when utilized by the librarian, show that a little effort can turn

a one-shot library instruction into an active library experience. Employing

these tactics can improve the students’ instruction quality and their learning

outcome.

Conclusion

Active

learning can take a student from a role of a listener into that of an initiator

in their own learning. This can dramatically affect the amount of information

retained from library instruction, particularly in one-shot classes which most

academic libraries now employ. With active learning, students are engaged in

their own education. With a bit of work to their curriculum and teaching style,

librar

|

| Source |

References

Bonwell, C.C. and Eison,

J.A. (1991). Active learning: creating excitement in the classroom. Washington

DC: The George Washington University (Eric Clearinghouse on Higher Education).

Drueke, J. (1992). Active

learning in the university library instruction classroom. Research Strategies, 10(Spring), pp. 77-83.

Holderied, A. (2011).

Instructional design for the active: Employing interactive technologies and

active learning exercises to enhance library instruction. Journal of

Information Literacy, 5(1), 23-32.

Johnson, D., Johnson. R.

and Smith. K. (1991). Active learning: Cooperation in the college classroom. Edina,

MN: Interaction Books.

Lorenzen, Michael.

(2001). Active Learning and Library Instruction. Illinois Libraries, 83(2),

19-24.

Mabnv. C. E. (1995). Using cooperative learning

principles in BI. Research strategies, 13(Summer),182-185.